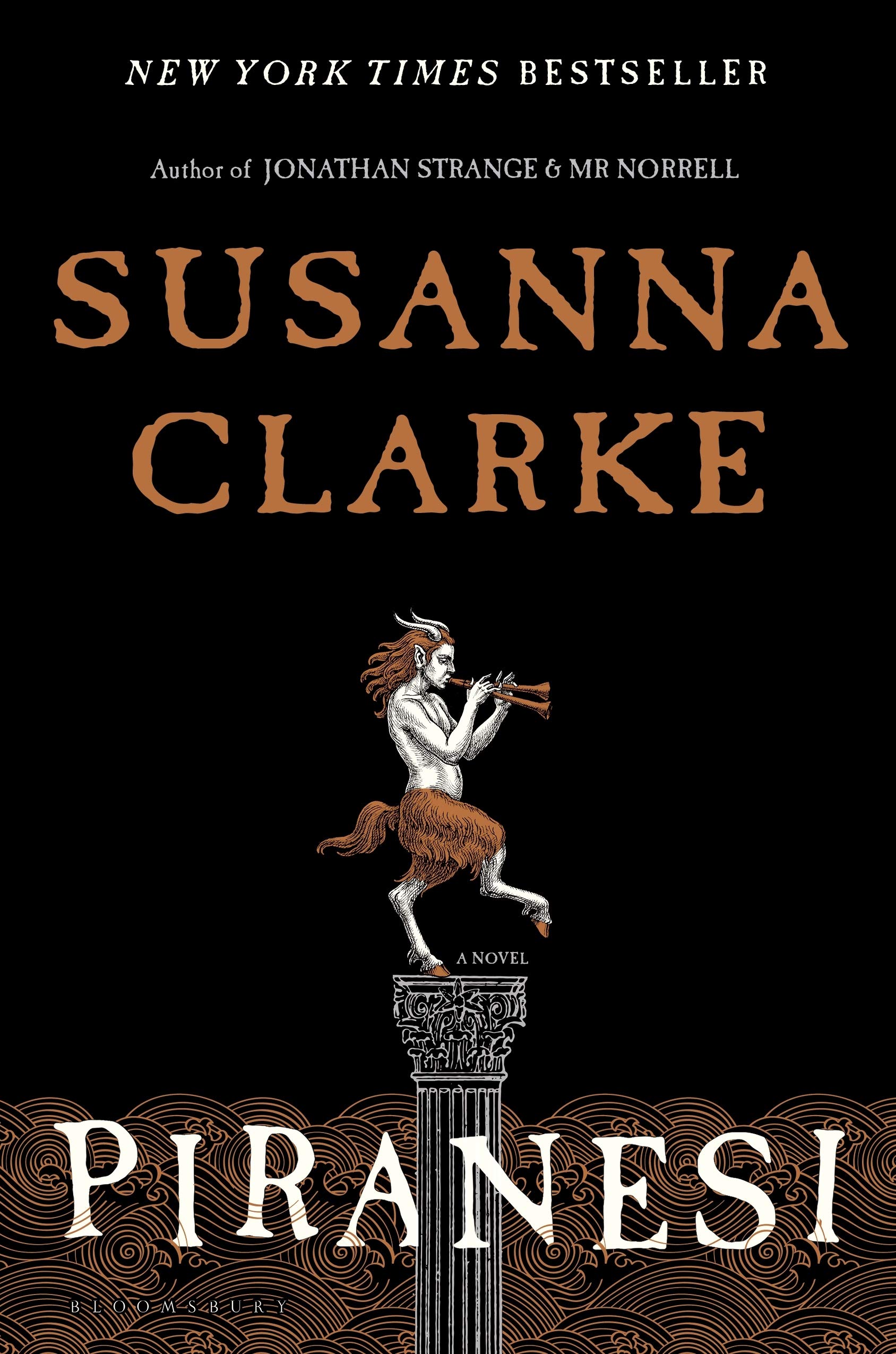

As with several other books I’ve reviewed here, the less you know going into Susanna Clarke’s PIRANESI, the better. If I were you, I’d go read it right now and come back here afterward. If you insist on knowing more before you commit, I will try to spoil as little as possible.

The novel is cast as a journal written by one of two inhabitants of a world that consists of a giant, labyrinthine “House.” The House is a seemingly infinite succession of vast marble halls, vestibules, and staircases, each filled with statues. The lower level opens onto an ocean where the narrator (named “Piranesi” by the other inhabitant, whom the narrator in turn refers to as “the Other”) gathers the kelp and catches the fish that sustain him. (Giovanni Battista Piranesi was an 18th century artist known for his etchings of labyrinths.)

The pace is perhaps too leisurely at first, as the narrator gives us a tour of his world and what he knows of its history. But just as I was starting to get impatient, the anomalies began to pile up. Journals bearing dates from 2011 and 2012. The Other wearing a neatly pressed three-piece suit. Very slowly, piece by piece, bits of what we consider the “real world” begin to intrude. Other characters appear and before long the plot becomes utterly compelling.

Clarke’s debut, the highly regarded JONATHAN STRANGE & MR NORRELL, was remarkable for its intelligence, its erudition, its period-conjuring prose, and the darkness beneath its glittery surface. PIRANESI is no less smart, learned, stylish, and unsettling. It functions admirably in literal terms but also carries allegorical heft. I see the House as an embodiment of mental illness, a prison that confines and isolates the narrator’s consciousness even as it provides a refuge from the chaos of consensual reality.

The novel is not entirely satisfying. It posits benign supernatural forces that strained my credulity. There are many parallel worlds in addition to ours and that of the House, but those are the only two we ever see. I’m pretty sure there are a number of dead bodies that are never accounted for. The narrator conveniently neglects to reread his earlier journal entries until late in the story.

These are minor complaints. Clarke so vividly brings the House to life–the booming of the tides below, the swooping birds, the towering marble statues, the echoing vastness of the place–that it feels permanently engraved in my mind. Likewise the narrator’s gradual yet inevitable fall from innocence. To Clarke’s great credit, she never downplays the emotional aspects of the story in favor of the intellectual ones. The House may be made of cold marble, but her characters are warm and alive.