The first time I heard Jimmy Wilsey was on the radio—Austin, 1987, on the cover version of “Heart Full of Soul” from Chris Isaak’s eponymous second album. I liked the singer well enough, but the guitar playing was what made me lunge to crank up the volume. Long, legato bends shimmering with echo, notes fading in from nowhere and dissolving into piercing harmonics, a lonely, mournful, desolate sound that soon moved into my CD player and stayed there.

It was four years later, on 17 April, 1991, that Isaak finally played a show in Austin. The venue was the Austin Opera House—not the fancy theater that the name implies, but a 1700-person room without seating, carpeting, or decorations—my idea of a great venue, and just the right size for most of the bands I saw there, from Crowded House to Steve Earle to the Replacements to Melissa Ethridge. But between the time Isaak had been booked into the Opera House and the night of the show, “Wicked Game” had become a huge hit on both MTV and radio and the club was mobbed.

At the time, I thought maybe that rush of success was responsible for some of the uglier things I saw that night. Isaak made vicious fun of Jimmy all night long, changing the lyrics of the songs to target Jimmy and telling insulting stories between numbers. After the encore he invited women from the audience to join him on stage, where they danced and sang with Isaak and he ogled them in return. The atmosphere was less rock show than frat party, and Jimmy seemed humiliated by the whole enterprise.

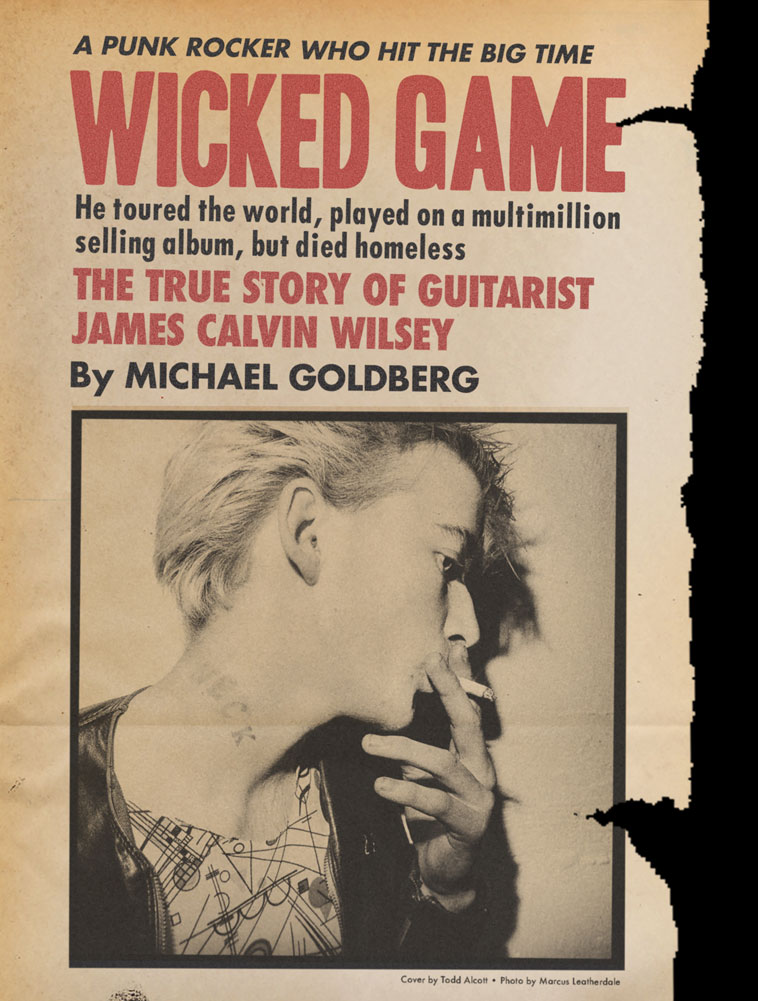

Now that I’ve read WICKED GAME, the excellent new biography of Jimmy Wilsey by his friend and fan Michael Goldberg, I know this was a regular occurrence—and far from the worst that Jimmy received at Isaak’s hands.

WICKED GAME is not a technically perfect book. There’s a lot of repetition, and some of his interviewees wander into the weeds. Goldberg tries to structure the story thematically as well as chronologically, leaving me unstuck in time in a couple of places. But at 410 pages of fine print, it feels complete. I got the gearhead stuff I that I love and the behind the scenes gossip I can’t resist. I felt like I knew all of these people, from his family to the friends from his days in the punk band The Avengers; from Isaak’s other backing musicians to Jimmy’s girlfriends, wife, and son; from the people who tried to save him to the ones who aided and abetted his addiction and death. I could see the heartbreaking arc of his life from beginning to end. I felt like I understood him. That is an astounding accomplishment for any biographer, and a gift to all of Jimmy’s fans.

The quality that people most seemed to remember about Jimmy was his sweetness. If, at the end, in the grip of a heroin addiction that he couldn’t control, he was willing to take advantage of anyone he could, this was the coda to a life where he was repeatedly generous and kind and thoughtful. Like Tim Hardin, or Janis Joplin, or Kurt Cobain, or so many others, the thing that was the core of his music, that made people respond so passionately to it, was a sensitivity that left him in deep emotional pain. His unwillingness—or inability—to confront the source of that pain—that source being life itself—cost him his life.

WICKED GAME is required reading for anyone who loved the anguished cry of Jimmy WIlsey’s guitar, and recommended to anyone who cares about the way that art is made.

[Note: As of this writing, the book is not available through Amazon.com. You can order from the publisher at https://hozacrecords.com/product/wicked-game/.]