“When I was growing up, I never felt like a whole person. I always thought there was something mentally wrong with me. I ran away from home a lot as a kid, looking for something. But I didn’t know what it was. There was something missing inside of me, I felt. I didn’t feel I was 100 percent human….Of course, not having a father had a lot to do with it. Being raised by a mother who had to work two jobs all her life had a lot to do with it. Being Black and born in the ghetto and not thinking that you can get out. That’s what most of us go through. Most Black people born in the United States today have a psychological defect. We’re born into something that’s not what we perceive life to be.

“We’re born in fucking ghettos of poverty, drugs, pimps, gangsters, prostitutes, guns. That is what you call mental illness. So from jump street, Black people are mental patients in the hospital of fucking life. A lot of Blacks don’t understand this. So I’m here to tell them: Look at it like it’s a mental hospital. And like in any hospital, the first thing you have to do is get well. And to get well, we have to say we are somebody, we are relevant to life, we can get out of here, and we don’t have to pick up guns and kill people and pimp our sisters. We don’t have to gangbang. And we can get out.”

—Rick James

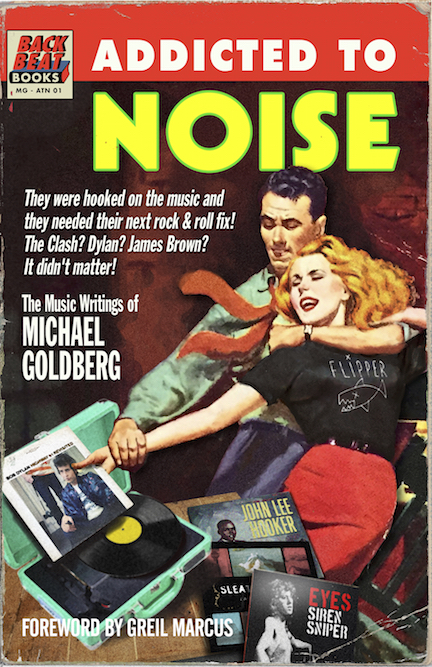

Yep, you read that right. That’s Rick James talking, from a new collection of interviews called ADDICTED TO NOISE by former ROLLING STONE Senior Writer Michael Goldberg. (I previously reviewed Goldberg’s biography of James Calvin Wilsey, WICKED GAME.) His forte is the extended profile, with a mixture of quotes from the artist, quotes from others, and commentary from Goldberg. The book also contains variations on the interview form such as barely edited Q&As and monologues, most of them less successful. The Q&As can be muddled and repetitious (the Patti Smith piece particularly needed a harsher edit), and some of the hostile interviews (e.g. with Zappa or Flipper or the Sex Pistols) are embarrassing to sit through, even vicariously.

But when he’s on, Goldberg can come up with a moving and insightful story that changes the way you see an artist. His Stevie Wonder profile is worth the price of the collection all by itself, if only for the moment when Wonder acknowledges his perpetual tardiness.

“People seldom have a real perspective on what it takes. They just go, ‘Damn, he took so long.’ They don’t realize all the many experiences you have to go through.

“People do not understand lots of times. Which is okay. I mean, I’m not saying people have to change their lives for me. But if I’m what they want to be involved with, if this situation means that, as opposed to being 3 o’clock, it’s gonna be 9 o’clock or 10 o’clock, and if during all of that time between when it was supposed to be and the time it’s gonna be, I am honestly dealing with something else, then that’s just what that is. I can’t say that a computer’s going to break down. Basically all you can do is the best you can do.”

Goldberg needs time and space to do his best work. When he has enough column inches and access to an artist for days at a time, he can come up with pieces like the one on Brian Wilson’s first solo album, where the walls come down and you really feel like you’re seeing into people’s hearts. He managed the same feat with Brian’s brother Dennis, even with the disadvantage of writing it after Dennis’s death.

Another highlight of the book is a close comparison of Dylan’s “Desolation Row” with Jack Kerouac’s DESOLATION ANGELS. I knew Dylan was a plagiarist (e.g. “With God on Our Side” swipes the melody from “The Patriot Game”; Dylan famously stole Dave Van Ronk’s arrangement of “House of the Rising Sun”) but this time it was personal. “Desolation Row” is my second-favorite Dylan song (after “Positively 4th Street”), and Goldberg’s case for Dylan’s looting is disappointingly persuasive.

Other highlights include an in-depth report on the death of San Francisco’s KSAN as a progressive free-form music station, and personality pieces on Chris Isaak and Michael Jackson.

I can’t imagine a reader who would enjoy everything in this overlong book. At the same time, I can’t imagine a serious music fan who wouldn’t find at least a few pieces to love, pieces that turn a distant icon into a living, feeling human being.