Bodie Kane, the first-person narrator of Rebecca Makkai’s brilliant and addictive new novel, I HAVE SOME QUESTIONS FOR YOU, is a producer of true-crime podcasts. One of the running motifs (I’m reluctant to call it a joke) in the book is how easy it is to be confused by the sheer number of acts of violence against women and girls that have come to light in these amateur investigations, from sexual assault to rape to murder, always perpetrated by men, who all too often get away with it.

From the first page:

“Wasn’t that the one where the guy kept her in the basement?

“No! No. It was not.

“Wasn’t it the one where she was stabbed in—no. The one where she got in cab with—different girl. The one where she went to the frat party, the one where he used a stick, the one where he used a hammer, the one where she picked him up from rehab and he…”

Bodie is also a film professor, so it’s no surprise when Granby, the boarding school where she attended grades 9-12, invites her to teach a “mini-mester” class in January of 2018, some twenty years after her graduation. Bodie volunteers to teach a class on podcasting as well, and one of the topics she suggests to her students is the murder of her classmate, Thalia, who was killed a few weeks before graduation.

For twenty years, Bodie had managed not to think too much about Thalia. They’d been roommates junior year, but were never close. Thalia was beautiful and popular and Bodie was an outsider. The one thing they had in common was Drama Club, where Bodie ran lights for Camelot and Thalia played Guinevere. An athletic trainer named Omar had been quickly identified as Thalia’s killer and was still in prison for it.

Then, in 2016, a video starts to make the rounds of the internet. There’s a shot of the Camelot curtain call, with time stamp, and an elaborate argument claiming that Omar could not have killed Thalia. Bodie, though disturbed by the idea that Omar might be innocent, manages to avoid worrying about it until one of her podcasting students decides to use Thalia’s murder for her class assignment. Bodie’s secrets, and those of many others, start getting dragged into the light.

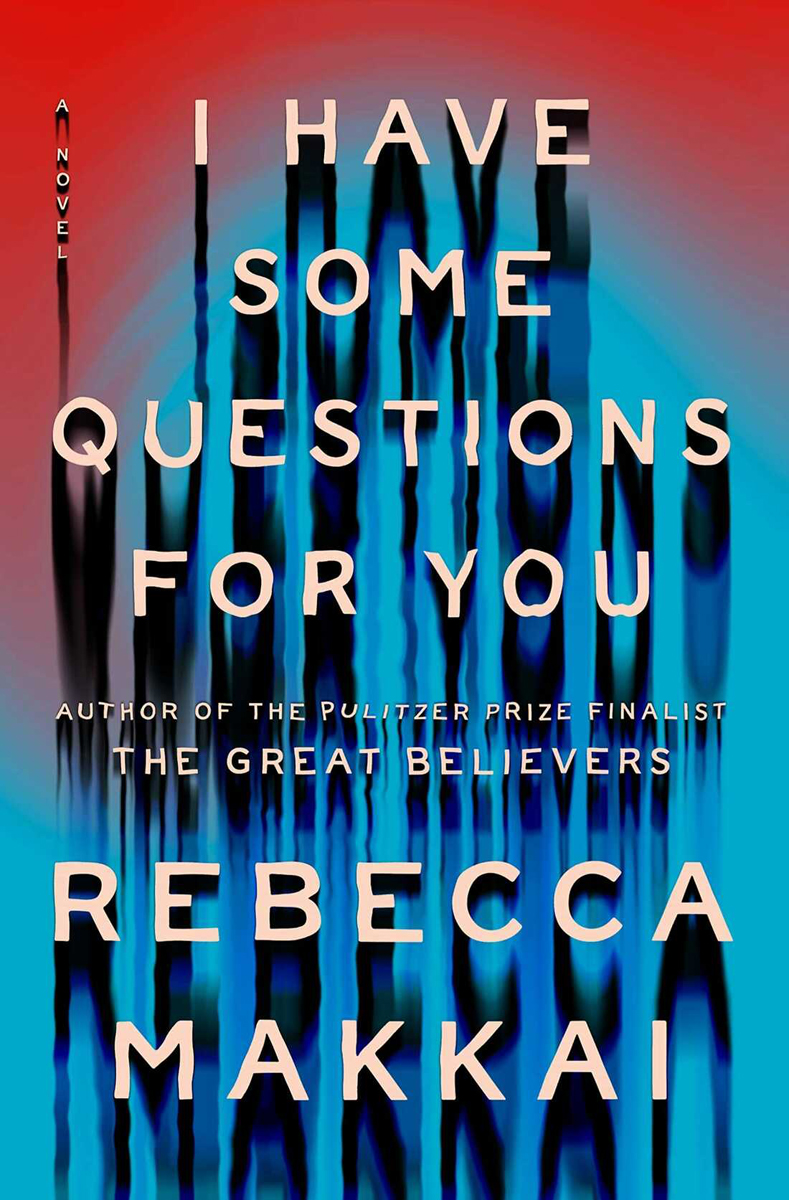

QUESTIONS, on the most basic level, is a whodunnit, but that’s just the starting point. It’s a classic coming-of-age campus novel that ranks with Donna Tartt’s SECRET HISTORY. It is up to the minute in its concern with male sexual predators, even as it shows how cancel culture can turn into vigilante injustice. It deals with the racism at the heart of the criminal justice system, and how ordinary, well-meaning citizens can become part of the problem.

But all of that makes QUESTIONS sound like a particularly well contrived genre novel rather than the serious work of literature that it is. Makkai’s previous novel, THE GREAT BELIEVERS, had the same kind of scope and ambition, dealing with the AIDS epidemic of the 80s at the same time that it talked about art and integrity and ambition. Both novels feature instantly memorable characters and clean, beautiful, hardworking prose.

Consider p. 354: “I said, ‘Look who drank the Flavor Aid.’” This is so perfectly Bodie—she knows that the followers at Jonestown drank Flavor Aid, not Kool-Aid, and she uses the correct name not to show off, but because she cares about getting things right. She tells us early on that she is a detail-oriented person, and Makkai, time after time, proves it without ever calling attention to it.

Makkai is not above a few literary games: Thalia’s name suggests Thanatos; Kane alludes to Bodie’s questioning whether she is her sister’s (roommate’s) keeper. The predatory music teacher who may also be a killer shares a last name with Robert Bloch, author of PSYCHO. I never found it distracting—as in Dickens, there are a lot of characters and I was glad for the appropriate names. And though there are a lot of characters in QUESTIONS, I felt Makkai trying, if not to love them all, to at least walk a mile or two in their shoes. This is most obvious in the chapters where Bodie tries to picture each of the suspects as they might have committed the murder.

One of the telltale indicators of literature vs. genre may be that very compassion that the author feels for her characters. In classic pulp, the villain is so purely evil that the hero doesn’t have to bother with compunctions about killing him, or worry about nightmares afterward. The situation in QUESTIONS is far more complicated, and gets more so as the story goes on. It’s a master class in the way character can drive plot even as plot reveals character.

Don’t miss I HAVE SOME QUESTIONS FOR YOU. The questions it asks are ones we should be shouting from the rooftops.