I haven’t met a lot of out-and-out unrepentant villains in my life. Some people I know started out with good intentions and got bitter. Some grew up hungry and never got over it. Yet popular fiction (including films) tends to favor the elemental, black-and-white, good-versus-evil conflict, winding the audience up until they’re ready to kill the bad guys with their own hands and teeth, building to a loud and bloody climax.

Nothing could be farther from the plot of THE CHOSEN. Potok gives us two fathers and two sons, each of whom is trying with all his heart to be the best person he can be, not just for himself or his family, but for the world. And all of them inflict terrible pain on each other.

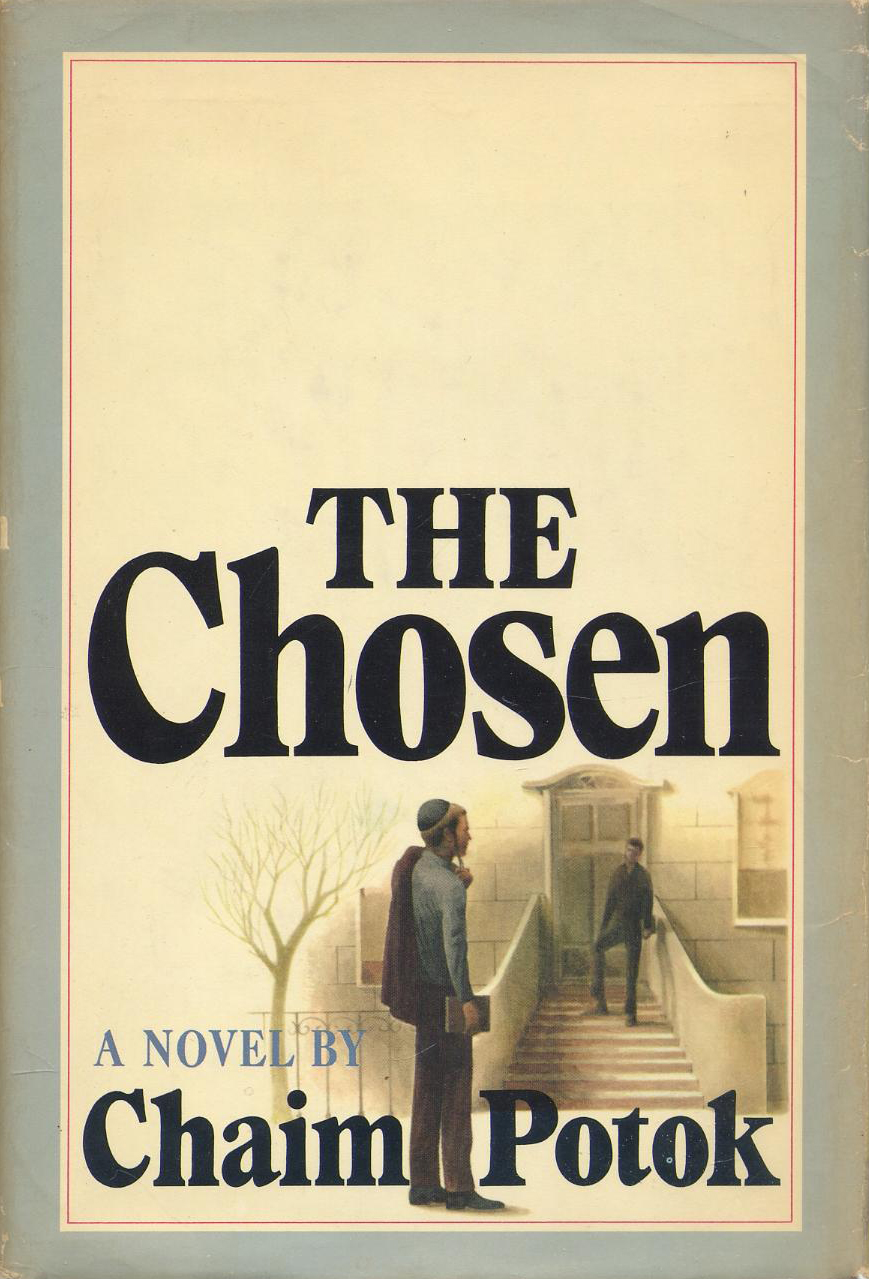

Reuven, the narrator, is the son of a prominent Modern Orthodox rabbi in Brooklyn, where he attends high school in the early days of World War II. In the course of a baseball game (fast pitch softball, to be precise), Reuven’s life intersects that of Danny Saunders, the son of a revered Hasidic rabbi. Both boys are gifted Talmudic scholars, Reuven by choice, Danny because his father’s position is hereditary, and he has no alternative.

Reb Saunders, Danny’s father, is physically intimidating, emotionally distant, brilliant, and demanding. His belief in his own correctness is as unswerving as his faith in ”the Master of the Universe.” Danny, equally stubborn, is drawn to psychology, a subject considered irrelevant at best to the Hasidim. He is reduced to keeping his studies secret from his father, and he’s helped by an unexpected ally.

In the course of the novel, we see through these characters’ eyes as the Holocaust is revealed, as the Zionist movement takes off, as the State of Israel is established. Danny and Reuven end up on opposite sides of the struggle between supporters of a religious versus secular state, a struggle that turns heated and finally violent. Because we are so invested in the characters, the political becomes personal for the reader as well, not least when the last revelations come out in the final pages.

Potok writes cleanly, vividly, and informatively, though at times he overuses oral formula, as when repeatedly describing the Hasidic traditional dress: “the dark suit, the dark skullcap, the white shirt open at the collar, and the fringes showing below the jacket.” The effect may be less than Homeric, but it does add a certain epic weight to the narrative.

Speaking of those final pages—bring Kleenex. Bring lots of Kleenex.